Which way will the wind blow?

Allianz Commercial Hurricane season outlook 2020

Summary

Hurricane season 2019 - Review

The 2019 hurricane season overall was slightly above average but not comparable to the record activity of 2017. The season counted 10 hurricanes, out of which six reached a major hurricane status. With three major hurricanes (category 3–5) in the Atlantic, 2019 was close to the long-term average (2.7). However, the number of named storms (18) significantly exceeded the average (12) and marks the ninth Atlantic hurricane season on record (since 1851) with 18+ Atlantic named storms [3]. Overall losses in the US during the 2019 season were $3bn, of which $2bn were insured. Due to the lack of severe hurricanes, the US share of global natural catastrophe losses were lower than normal – 31% of overall global losses compared with the long-term average of 35%) [4].

The climatological peak months of last year’s (2019) hurricane season started off with a quiet August. September was very active and the main driver of the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season. October was characterized by above-average named storm activity but below-average hurricane activity [5].

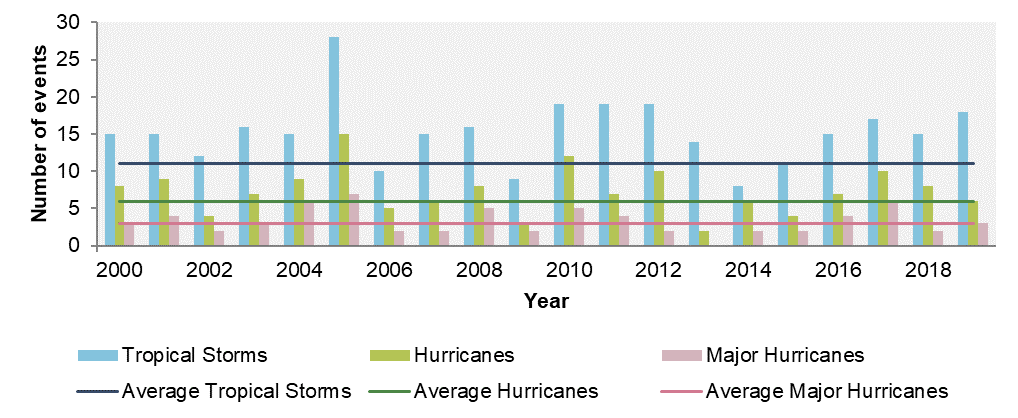

Atlantic Hurricane seasons by the numbers: 2000 to 2019*

The 2019 Atlantic hurricane season will primarily be remembered for Hurricane Dorian, which devastated the northwestern Bahamas at Category 5 intensity and further impacted the southeastern United States. Tropical Storm Imelda also deluged southeast Texas with tremendous amounts of rainfall, causing considerable damage in the process [6].

Exceeding the previous record of Hurricane Irma in 2017, Dorian is considered to be the strongest hurricane ever recorded in the open Atlantic, outside of the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. After crossing the US Virgin Islands as a category 1 hurricane on August 28, Hurricane Dorian rapidly intensified into a category 5 hurricane and made landfall on the Bahamas Great Abaco Island on September 1 with peak wind speeds of about 180mph (290kph). Hurricane Dorian is the strongest hurricane on record to make landfall in the Bahamas. In addition to its fierce wind, Dorian brought an estimated storm tide of up to 25ft (7.6m) and released up to 39in (1000mm) of rain over the Bahamas. Dorian was downgraded to a category 2 storm as it began moving north towards North Carolina. Originally, it was feared that it would hit the southeast coast of the US, but a more northerly and easterly track largely spared the US mainland. Dorian again made landfall in the Atlantic Provinces of Canada on September 7. Total economic losses attributed to Dorian were about $5.6bn, with $4bn in insured losses [7].

Tropical cyclones that are very destructive and/or deadly can be retired by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) from future Atlantic tropical cyclone name lists, which otherwise are repeated every six years. Through 2018, nearly 90 Atlantic hurricane or tropical storm names had been retired. Despite its disastrous 2019 impacts, Dorian will not be the latest addition to the retired list for now. The WMO usually holds a weeklong meeting every spring to consider deleting a name, but, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, this year's meeting was turned into a shortened videoconference which did not leave room for discussion about the potential retirement of any names from the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season. Dorian might be eliminated in spring 2021 when the next meeting will take place [8].

Accuracy of pre-season forecasts in 2019

Hurricane Season 2020

The initial extended-range forecast of the Atlantic seasonal hurricane activity for 2020 by CSU describes the following factors that lead to the conclusion of a slightly above average season.

El Niño and La Niña are opposing phases of what is known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. The associated complex weather patterns result from variations in ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific. ENSO has an influence on the hurricane formation both in the Atlantic and the Eastern Pacific Basin. El Niño (warm phase) is based on warmer than usual sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific. Simply put, El Niño favors stronger hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific basins, and suppresses it in the Atlantic basin. Conversely, La Niña which is characterized by colder temperatures in the equatorial Pacific, suppresses hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific basins, and enhances it in the Atlantic basin. These impacts are primarily caused by changes in the vertical wind shear and changes in wind speed and direction between roughly 5,000 to 35,000 ft. above the ground. Strong vertical wind shear can suppress a developing hurricane [9].

Current warm neutral El Niño conditions appear likely to transition to cool neutral El Niño or potentially even weak La Niña conditions by this summer or fall of 2020. The tropical Atlantic is warmer than normal, while the subtropical Atlantic is quite warm, and the far North Atlantic is anomalously cool. The anomalously cold sea surface temperatures in the far North Atlantic lead us to believe that the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO) is in its negative phase. The AMO is correlated to air temperatures and rainfall over much of the Northern Hemisphere, in particular in the summer climate in North America and Europe, and is also associated with changes in the frequency of North American droughts and is reflected in the frequency of severe Atlantic hurricane activity. The cold phase of the AMO is associated with low-activity eras (such as the period 1971-1994). A key atmospheric feature of the corresponding AMO warm phase is a stronger West African monsoon. Although, a cold far North Atlantic is typically associated with a cold tropical Atlantic, that has not occurred this winter and consequently most of the tropical Atlantic is warmer than normal [10].

It is assumed that the cold phase of the AMO with above normal tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures is not able to counterbalance the effect of the weak La Niña in this upcoming hurricane season. Therefore, an above-average probability for major hurricanes making landfall along the continental United States coastline and in the Caribbean is anticipated.

The skill of hurricane season forecasting increases as the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season approaches, with uncertainty dropping.

Outlook: Above-average Hurricane Season

Hurricane season 2020: predictions by institution

Swipe to view more

|

Source*

|

Forecast publish date

|

Tropical storms**

|

Hurriances**

|

Major Hurricanes**

|

US Storm landfalls**

|

US Hurricane landfalls**

|

Rating

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSR (long-term norm: 1950-2019) | 11 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | Long term normal | |

| Comparison: 2019 average Hurricane season forecast | 13.1 | 5.6 | 2.5 | 2 | 1 | Near normal | |

| Comparison: 2019 Hurricane season actual | 18 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | Above average | |

| 2020: Forecast range | 14-22 | 7-11 | 2-6 | 4 | 2-4 | Above normal | |

| AccuWeather* | March 26 | 14-18 | 7-9 | 2-4 | - | 2-4 | Above average |

| CSU* | April 2 | 16 | 8 | 4 | - | - | Above average |

| TSR* | April 7 | 15 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 2 | Above average |

| NCSU* | April 17 | 18-22 | 8-11 | 3-5 | Above average | ||

| NOAA* | May 21 | 13-19 | 6-10 | 3-6 | Abover average | ||

| CSU*^ | June 4 | 19 | 9 | 4 | Above average | ||

| TSR*^ | May 28 | 17 | 8 | 3 | Above average |

Source: AGCS

“Will this hurricane season in the Atlantic basin be an active one or will it be a normal year? While we don't know for sure, of course, the overall number of hurricane-strength storms is likely to be in line with the long-term average, according to an analysis of early forecasts,” says Carina Pfeuffer, Catastrophe Risk Analyst at AGCS.

“While actual storm activity is very difficult to predict, there remains a possibility for high losses during the 2020 season. All it takes is one extremely powerful hurricane to hit a major urban area to produce devastatingly high losses. Therefore, it is extremely important that businesses located in hurricane-prone areas should take mitigation measures against the risk of wind, water and storm surge and have an adequate continuity plan in place just in case – not only this season, but each and every year.”

[2] Bloomberg, Hurricane Harvey was second most expensive storm in US history, January 25, 2018

[3] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): Hurricanes and Tropical Storms - November 2019, November 2019

[4] Munich Re, Tropical cyclones causing billions in losses dominate nat cat picture of 2019, January 8, 2020

[5] Colorado State University (CSU): Summary of 2019 Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Activity and verification of author’s seasonal and two-week forecasts, November 27, 2019

[6] CSU

[7] Scientific American: A Review of the Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2019, November 24, 2019

[8] The Weather Channel: Why 2019's Hurricane Dorian Wasn't Retired by the World Meteorological Organization, April 1, 2020

[9] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Impacts of El Niño and La Niña on the hurricane season, May 30, 2014

[10] CSU, Extended-Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity for 2020, April 2, 2020

[11] Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), April forecast update for North Atlantic hurricane activity in 2019, April 5, 2018